Tugendhat House

Brno, Friday, September 6, 2024

STUMBLING STONES IN MEMORY OF THE HOŽE, LÖW-BEER AND TUGENDHAT FAMILIES

In a ceremonial act on Friday, September 6, 2024, stumbling blocks were inaugurated in front of six houses in the area of Drobneho / Park Street, Antonína Slavíka / Beischlägergasse and Černopolní / Schwarzfeld Street in Brno, commemorating more than 20 fellow citizens who were expelled and murdered by the Nazis for racist reasons because they were Jews.

The stumbling blocks on the sidewalk in front of the house of the expelled and murdered former Jewish residents and Czechoslovak citizens document their names and the dates of their birth and death.

These families also lost their property to the Nazis. After the Second World War, their property was not returned to them. Three of the houses are museums and are among the most important tourist attractions in Brno. The Tugendhat House has been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 2001.

Among the numerous visitors to the six ceremonies were high-ranking representatives of public life, including

• Petr Fiala, Prime Minister of the Czech Republic

• Vlastimíl Válek, Deputy Prime Minister of the Czech Republic

• Mikuláš Bek, Minister of Education, Youth and Sports;

• Jan Grolich, Governor of South Moravia

• Markéta Vaňková, Lord Mayor of Brno

• Martin Maleček, Mayor of Brno North

• Petra Dachtler, Deputy Ambassador of the Federal Republic of Germany

• Zbyněk Šolc, General Director of the Brno City Museum

• Vladimír Březina, Deputy Director of the Brno Regional Museum

• Karol Sidon, Chief Rabbi of the Czech Republic

• Jáchym Kanarek, Chairman of the Brno Jewish Community

• Eva Yildizová, Director of the STETL Fest Brno

• Zuzana Palicová, Director of the Bratislava City Museum

• Eva Lustigová, Director of the Arnošt Lustig Foundation

• Petr Kalousek, Director of the Meeting Brno Festivals

• Mojmír Jeřábek, former director of the Czech Center Vienna.

The following descendants of the survivors took part:

From Austria:

• Daniela Hammer-Tugendhat, youngest daughter of Grete and Fritz Tugendhat, builders of the Tugendhat House (Cernopolní 45), her husband

• Ivo Hammer-Tugendhat and their two sons

• Matthias Hammer and

• Lukas Hammer with his daughters

• Anouk and

• Naima

From the USA the children of Herbert Tugendhat, who was born in the Tugendhat House, and Katherine Tugendhat-Logan:

• Eduardo Tugendhat with daughter

• Sara

• Marcia Tugendhat

• Andrés Tugendhat and his wife

• Karin Tugendhat

From Switzerland:

• Daniel Low-Beer, grandson of Walter Löw-Beer, owner of the wool factory in Brünnlitz / Brněnec, made famous by the film Schindler's List

From the Czech Republic

• Alexej Zinner, Descendant of Pauline Zinner, née Tugendhat, aunt of Fritz Tugendhat. She lived in the house Drobného 18.

Organization:

The stumbling blocks and the ceremonial act of inauguration were organized by

• Museum of the City of Brno (General Director Zbiněk Šolc) together with

• Meeting Brno (Director Petr Kalousek),

• Museum Brno (Vladimír Březina), the

• STETL Fest (Eva Yildizová) and the

• Jewish Community of Brno (Jáchym Kanarek)

The initiators of the stumbling blocks are Veronika Smyslová, director of the Arnold House / Department of the Brno City Museum and Michal Doležel, Brno City Museum.

Historical research: Michal Dolezel, Peter Houzar, Veronika Wihodová, Kateřina Kalvodová, Silvia Klimešová, Jana Bělkovská, Lucie Valdhansovoá, Jáchym Kanarek, Ivo Hammer, Michael Lambek, Jacqueline Solway, Marcia Tugendhat, Ema Přikrylová, Jana Nešporová and Oldřich Smysl.

Ceremonial act

The act of opening the stumbling blocks began in front of the Arnold House with its Cecilie and Cornel Hože garden. The dignified ceremony included the unveiling of the stumbling blocks, the reading of the names and dates (by Michal Doležel), prayers and the laying of roses by the speakers and descendants of the families. The ceremonies were accompanied by touching music by Hana Bednaríková (violin) and – in front of the Tugendhat House – also by Ester Yildizová (singing).

After the speeches by Prime Minister Petr Fiala, Minister Mikuláš Bek, Governor Jan Grolich, Lord Mayor Markéta Vaňková, General Director Zbiněk Šolc, Chairman of the Jewish Community of Brno Jáchym Kanarek, Lukas Hammer, grandson of Grete and Fritz Tugendhat and member of the Austrian National Parliament (Greens), gave a speech which is documented here. (The speech was given in English and translated into Czech on site by Katka Báňová).

Lukas Hammer: Speech at the opening of the Stolpersteine. Brno 6.9.2024

Dear members of government

Dear family

Dear ladies and gentlemen!

During our first visit together to Brno, I was 7 years old, and I can only remember one thing. My then seriously ill aunt Hanna stood in her former childhood room for the first time since her escape. When she tried to open the door to the terrace, the caretaker yelled at her so harshly that she flinched. It was as if she had been expelled from her home for a second time.

She was not welcome and unwanted in the house. We often felt this way in the following years. Even more: on several occasions, during official tours of the house, it was explained upon inquiry that no one from the family had survived. Perhaps because the following question might have been uncomfortable to answer. The question of why it was decided that not a single one of the houses will be returned to the families.

Today, stumbling stones are being laid in the ground in front of the houses of our displaced and murdered relatives. To remember the family and the people who lived here until the Nazi terror. Who had their homes here. For us as a family, these houses are primarily not cultural sites, but a home. A home where we would have played in the garden with our relatives as children. Places where we would have returned together as a large family.

When the Tugendhat and Löw-Beer families were invited to come to Brno seven years ago, we felt this way for the first time. Over 100 members of our family from four continents, who in some cases didn't even know each other before, gathered in the garden of my grandparents. It was also a strong sign that not only were people expelled and murdered here, but that many survived.

I am infinitely grateful to the organizers of Meeting Brno for these moments. It fills me with joy to see that there are indeed so many people in Brno who are committed to an active culture of remembrance in various ways. For whom remembrance is more than just a symbolic act, where one thinks about completed events in the past. I have met so many committed people in and from Brno who are grappling with their own responsibility and history - many of which are here today. Who are asking themselves what all of this has to do with us today and who don’t want to make it too easy for themselves.

The stumbling stones remind us of who once lived here and what happened to them. Like, for example, in the Antonina Slavíka 9, where Renate Schwarz, my mother's cousin, lived. Renate was 13 years old when she, like her brother Thomas and her parents Lise and Richard, was murdered in the gas chambers of the Nazis.

But hopefully, the stumbling stones will also provoke thought.

What happened to these people and their families who once lived here? How could it come to the point where people were so consumed by hate that they deliberately murdered children like Renate in gas chambers? What must happen beforehand in a society and in the people within it? How can we prevent this from ever happening again? How did it start, and what does it have to do with us and with me today?

Last Sunday, the openly far-right AfD received over 30 percent in state elections in two German states. In many other European countries, far-right and post-fascist parties are on the rise. This time, the hate is directed against refugees and people from Afghanistan, Syria, or the African continent.

For me, "Never Again" does not mean "never again to us Jews." It means never again to any human being. Never again denying people their humanity, never again racism against any group, never again politics driven by hate, prejudice, and incitement.

It never begins with murder; it begins with words, with playing on fear and anger. With opportunism and indifference.

In this sense, I hope that the stumbling stones being laid in the ground today will contribute to reflecting on the crimes that people are ultimately capable of and how we can counter the dehumanization of others.

STOLPERSTEINE / Stumbling Stones

Drobného / Parkstraße 26, Arnold House, Cecilie and Cornel Hože - Garden

Cecilie was an aunt of Grete Tugendhat

|

ZDE ŽILA CECILIE HOŽE ROZ. LÖW-BEER NAR. 11. 6. 1864 DEPORTOVÁNA 12. 5. 1942 DO TEREZÍNA ZAVRAŽDENA 7. 9. 1942 V TEREZÍNĚ

|

HERE LIVED CECILIE HOŽE NÉE LÖW-BEER BORN ON 11. 6. 1864 DEPORTED ON 12. 5. 1942 TO THERESIENSTADT MURDERED ON 7. 9. 1942 IN THERESIENSTADT

|

|

ZDE ŽIL MAX HOŽE NAR. 4. 10. 1888 DEPORTOVÁN 12. 5. 1942 DO TEREZÍNA ZAVRAŽDĚN 23. 6. 1942 V MAJDANKU

|

HERE LIVED MAX HOŽE BORN ON 4. 10. 1888 DEPORTED ON 12. 5. 1942 TO THERESIENSTADT MURDERED ON 7. 9. 1942 IN MAJDANEK

|

|

ZDE ŽILA FRIEDERIKE HOŽE ROZ. KESSLER NAR. 15. 12. 1896 DEPORTOVÁNA 12. 5. 1942 DO TEREZÍNA ZAVRAŽDĚNA 1942 V LUBLINU

|

HERE LIVED FRIEDERIKE HOŽE NÉE KESSLER BORN ON 15. 12. 1896 DEPORTED ON 12. 5. 1942 TO THERESIENSTADT MURDERED ON 7. 9. 1942 IN LUBLIN

|

Drobneho / Parkstraße 22, Alfred und Marianne Löw-Beer House

Alfred und Marianne Löw-Beer are the parents of Grete Tugendhat

|

ZDE ŽIL ALFRED LÖW-BEER NAR. 16. 5. 1872 ZEMŘEL ZA NEZNÁMÝCH OKOLNOSTÍ BĚHEM ÚTĚKU PŘED NACISTY 10. 4. 1939 NALAZEN NA KOLEJIŠTI U STŘÍBRA

|

HERE LIVED ALFRED LÖW-BEER BORN ON 16.05.1872 HE DIED UNDER UNKNOWN CIRCUMSTANCES WHILE FLEEING FROM THE NAZIS HE WAS FOUND ON 10.04.1939 ON THE RAILWAY TRACKS NEAR STŘÍBRA

|

|

ZDE ŽILA MARIANNE LÖW-BEER ROZ. WIEDMANN NAR. 2. 9. 1882 UPRCHLA PŘED NACISTY V ROCE 1939 ZEMŘELA 16. 11. 1975 V ST. GALLENU

|

HERE LIVED MARIANNE LÖW-BEER NÉE WIEDMANN BORN ON 09.02.1882 SHE FLEW FROM THE NAZIS IN 1939 SHE DIED ON 16.11.1975 IN ST. GALLEN

|

|

ZDE ŽIL MAX LÖW-BEER NAR. 11. 4. 1902 UPRCHL PŘED NACISTY V ROCE 1939 ZEMŘEL 7. 4. 1954 VE VANCOUVERU

|

HERE LIVED MAX LÖW-BEER BORN ON APRIL 11, 1902 HE FLEW FROM THE NAZIS IN 1939 HE DIED ON APRIL 7, 1954 IN VANCOUVER

|

|

ZDE ŽIL HANS LÖW-BEER NAR. 22. 2. 1911 UPRCHL PŘED NACISTY V ROCE 1939 ZEMŘEL 8. 5 1993 V MONTREALU

|

HERE LIVED HANS LÖW-BEER BORN ON FEBRUARY 22, 1911 HE FLEW FROM THE NAZIS IN 1939 HE DIED ON MAY 8, 1993 IN MONTREAL

|

Drobného / Parkstraße 18, Hans und Wilhelmina Tugendhat House

Hans Tugendhat was a brother of Fritz Tugendhat

|

ZDE ŽIL HANS TUGENDHAT NAR. 23. 9. 1894 UPRCHL PŘED NACISTY ZEMŘEL 1979 V TORONTU

|

HERE LIVED HANS TUGENDHAT BORN ON SEPTEMBER 23, 1894 HE FLEW FROM THE NAZIS HE DIED IN 1979 IN TORONTO

|

|

ZDE ŽILA VILEMINA MARIANA AUGUSTATUGENDHAT ROZ. HERRNRITT NAR. 2. 2. 1903 UPRCHLA PŘED NACISTY ZEMŘELA PO 1993 V TORONTU

|

HERE LIVED VILEMINA MARIANA AUGUSTA TUGENDHAT NÉE HERRNRITT BORN ON FEBRUARY 2, 1903 SHE FLEW FROM THE NAZIS SHE DIED IN 1993 IN TORONTO

|

|

ZDE ŽIL PETER CLAUS TUGENDHAT NAR. 29. 10. 1925 UPRCHL PŘED NACISTY V ROCE 1939 ZEMŘEL 1981 V CARACASU

|

HERE LIVED PETER CLAUS TUGENDHAT BORN ON OCTOBER 29, 1925 HE FLEW FROM THE NAZIS IN 1939 HE DIED IN 1981 IN CARACAS

|

Antonína Slavíka / Beischlägergasse (Na Kopečku) 9, Richard und Lisa Schwarz House

Lisa Schwarz was Fritz Tugendhat's favorite sister

|

ZDE ŽILA LISE SCHWARZ ROZ. TUGENDHAT NAR. 27. 11. 1900 DEPORTOVÁNA 28. 1. 1942 ZAVRAŽDĚNA PO 13. 6. 1942 V OSVĚTIMI

|

HERE LIVED LISE SCHWARZ NÉE TUGENDHAT BORN ON 27. 11. 1900 DEPORTED ON 28. 1. 1942 MURDERED ON 13. 6. 1942 IN AUSCHWITZ

|

|

ZDE ŽIL RICHARD SCHWARZ NAR. 7. 7. 1887 DEPORTOVÁN 28. 1. 1942 ZAVRAŽDĚN PO 13. 6. 1942 NA NEZNÁMÉM MÍSTĚ

|

HERE LIVED RICHARD SCHWARZ BORN ON 7. 7. 1887 DEPORTED ON 28. 1. 1942 MURDERED ON 13. 6. 1942 IN AN UNKNOWN LOCATION

|

|

ZDE ŽIL THOMAS SCHWARZ NAR. 10. 4. 1926 DEPORTOVÁN 28. 1. 1942 ZAVRAŽDĚN 4. 9. 1942 V MAJDANKU

|

HERE LIVED THOMAS SCHWARZ BORN ON APRIL 10, 1926 DEPORTED ON JANUARY 28, 1942 MURDERED ON SEPTEMBER 4, 1942 IN MAIDANEK

|

|

ZDE ŽILA RENATE SCHWARZ NAR. 20. 3. 1929 DEPORTOVÁNA 28. 1. 1942 ZAVRAŽDĚNA PO 13. 6. 1942 NA NEZNÁMÉM MÍSTĚ

|

HIER WOHNTE RENATE SCHWARZ GEBOREN AM 20. 3. 1929 DEPORTIERT AM 28. 1. 1942 ERMORDET AM 13. 6. 1942 AN EINEM UNBEKANNTEN ORT

|

Antonína Slavíka / Beischlägergasse (Na Kopečku) 13, Benno und Germaine Tugendhat House

Benno was an uncle of Fritz Tugendhat

|

ZDE ŽIL BENNO TUGENDHAT NAR. 2. 9. 1877 PŘED DEPORTACÍ DO KONCENTRAČNÍHO TÁBORA SE ZASTŘELIL 10. 1. 1942

|

HERE LIVED BENNO TUGENDHAT BORN ON SEPTEMBER 2ND, 1877 BEFORE BEING DEPORTED TO A CONCENTRATION CAMP, HE SHOT HIMSELF ON JANUARY 10TH, 1942

|

|

ZDE ŽILA GERMAINE LEODIE CESARIE TUGENDHAT ROZ. MONNIN NAR. 20. 9. 1880 UPRCHLA PŘED NACISTY ZEMŘELA 30. 11. 1985 VE VÍDNI

|

HERE LIVED GERMAINE LEODIE CESARIE TUGENDHAT NÉE MONNIN BORN ON SEPTEMBER 20, 1880 SHE FLEW FROM THE NAZIS SHE DIED ON NOVEMBER 30, 1985 IN VIENNA

|

|

ZDE ŽIL RENÉ ERIC TUGENDHAT NAR. 27. 7. 1909 UPRCHL PŘED NACISTY ZEMŘEL 1987 V BUENOS AIRES

|

HERE LIVED RENÉ ERIC TUGENDHAT BORN ON 27 JULY 1909 HE FLEW FROM THE NAZIS HE DIED IN 1987 IN BUENOS AIRES

|

|

ZDE ŽILA ANNA MARIE TUGENDHAT NAR. 11. 6. 1914 UPRCHLA PŘED NACISTY ZEMŘELA NEZNÁMO KDE

|

HERE LIVED ANNA MARIE TUGENDHAT BORN ON 11. 6. 1914 SHE FLEW FROM THE NAZIS SHE DIED IN AN UNKNOWN PLACE

|

Černopolní / Schwarzfeldstraße 45, Tugendhat House

|

ZDE ŽILA GRETE TUGENDHAT ROZ. LÖW-BEER NAR. 16. 5. 1903 UPRCHLA PŘED NACISTY V ROCE 1938 ZEMŘELA 10. 12. 1970 V ST. GALLENU

|

HERE LIVED GRETE TUGENDHAT NÉE LÖW-BEER BORN ON 16. 5. 1903 SHE FLEW FROM THE NAZIS IN 1938 SHE DIED ON 10. 12. 1970 IN ST. GALLEN

|

|

ZDE ŽIL FRITZ TUGENDHAT NAR. 10. 10. 1895 UPRCHL PŘED NACISTY V ROCE 1938 ZEMŘEL 22. 3 1958 V ST. GALLENU

|

HERE LIVED FRITZ TUGENDHAT BORN ON 10. 10. 1895 HE FLEW FROM THE NAZIS IN 1938 HE DIED ON 22. 3. 1958 IN ST. GALLEN

|

|

ZDE ŽILA HANNA LAMBEK ROZ. WEISS NAR. 29. 11. 1924 UPRCHLA PŘED NACISTY V ROCE 1938 ZEMŘELA 4. 1. 1991 V MONTREALU

|

HERE LIVED HANNA LAMBEK NÉE WEISS BORN ON 29. 11. 1924 SHE FLEW FROM THE NAZIS IN 1938 SHE DIED ON 4. 1. 1991 IN MONTREAL

|

|

ZDE ŽIL ERNST TUGENDHAT NAR. 8. 3. 1930 UPRCHL PŘED NACISTY V ROCE 1938 ZEMŘEL 13. 3. 2023 VE FREIBURGU IM BREISGAU

|

HERE LIVED ERNST TUGENDHAT BORN ON MARCH 8, 1930 HE FLED FROM THE NAZIS IN 1938 HE DIED ON MARCH 13, 2023 IN FREIBURG IM BREISGAU

|

|

ZDE ŽIL HERBERT TUGENDHAT NAR. 24. 2. 1933 UPRCHL PŘED NACISTY V ROCE 1938 ZEMŘEL 30. 8. 1980 V CARACASU |

HERE LIVED HERBERT TUGENDHAT BORN ON FEBRUARY 24, 1933 HE FLEW FROM THE NAZIS IN 1938 HE DIED ON AUGUST 30, 1980 IN CARACAS |

After the Ceremony

Lectures

4 April 2023: Brno, Opening of the garden

21 November 2022: Brno, High-level gathering, NEB, panel

February,4, 2021: Chicago, IIT, The Mies van der Rohe Society (zoom)

Ivo Hammer, Mental Opening. Reopening of the Garden as spatial restoration of the historical situation (Brno, April 5, 2023)

April 5, 2023

Re-opening oft he garden

Invitation by the director of the Brno City Museum, Mag. Zbyněk Šolc

Speeches by JUDr. Markéta Vaňková, Lord Mayoress of the Statutory City of Brno; Mgr. Jan Grolich Governor of the South Moravian Region

Ivo Hammer

Speech at the opening of the garden of the Tugendhat House

Madam Lord Mayoress!

Mr Region Governor!

Mr Director!

Ladies and gentlemen!

My name is Ivo Hammer, I am the husband of Daniela Hammer-Tugendhat, the youngest daughter of Grete and Fritz Tugendhat, the builders of the Tugendhat house.

I would like to thank Director Šolc for inviting me to this enjoyable event. I see the invitation as a sign of the appreciation the Brno City Museum has for the family.

Ernst Tugendhat died on March 13, 2023. In the words of the President of the Federal Republic of Germany, Frank Walter Steinmeier, Ernst Tugendhat was “one of the most important philosophers of the post-war period, whose thinking revolutionized and shaped German philosophy.” On behalf of the family, I would like to thank the city of Brno and the museum for the condolences the city of Brno.

Ernst Tugendhat was the last of the Löw-Beer and Tugendhat families to live in the Löw-Beer and Tugendhat houses that belonged to this garden.

I would also like to take this event as an opportunity to commemorate Grete Tugendhat's father, Alfred Löw-Beer, who was murdered near Pilsen in April 1939 while fleeing from the Nazis.

I am happy about the opening of the fence between the two houses Löw-Beer and Tugendhat. This opening restores spatially the historical situation. It is not generally known that Alfred and Marianne Löw-Beer only gave their daughter Grete the building land and the building costs of the Tugendhat house as an anticipation of their inheritance on the occasion of her marriage to Fritz Tugendhat. The rest of the garden, including the area of the former Belvedere, remained the property of Grete's parents. Fritz Tugendhat's photos, which are published in our book, document the use of this garden, also as a playground for the children, in summer splashing around with the water sprinkler, in winter tobogganing on the slope that seems to have been made for this purpose.

I also like to remember the family reunion in May 2017. Within the framework of the Brno meeting, the city of Brno invited three families from the Jews who survived the Shoa, who were important for the city's cultural life before 1938: the families Löw-Beer, Tugendhat and Stiassny. We had expected around 40-50 people, more than 120 came. The meeting of the families in the garden, in glorious weather, with the children playing and live music by Andrea and Jonas created beautiful but also ambivalent emotions.

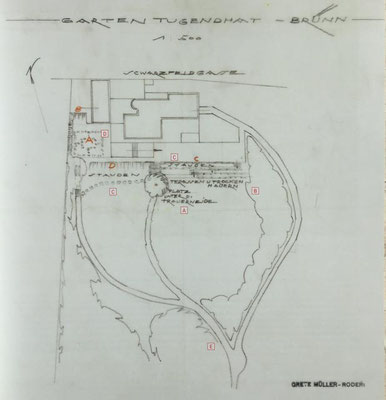

The iconic photos by Rudolf de Sandalo from 1931 present the house as a solitary cube, deserted and without vegetation. The photos by Fritz Tugendhat, originating from the few years that followed that the family was able to live in their house, document the material reality of life in the house, its temporality, its aging, the vegetation and the busy landscaped garden. The photos show on the one hand the intimate connection between architecture and nature intended by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, of geometric clarity and organic liveliness, and on the other hand what Mies van der Rohe called the meaningful emptiness of the landscape garden designed by the famous Czech garden architect Grete Müller-Roder in collaboration with Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and probably also Lilly Reich.

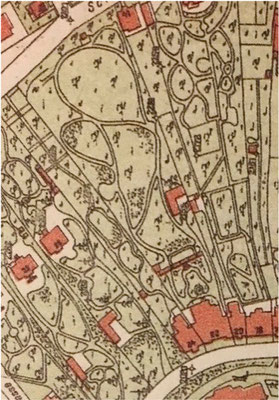

In the 18th century these hills above the Ponávka River were vineyards, partly interspersed with fruit trees. Apparently, in the 1920s, these vineyards were abandoned and a viewpoint called Belvedere was set up. The brick manufacturer Antonin Rüdiger Deycks bought the property in 1854, set up a greenhouse and probably also had trees planted in the park.

The Art Nouveau villa built in 1904 according to plans by Alexander Neumann for the manufacturer Moritz Fuhrmann also included the carriage house with an angular floor plan and also a garden with fountain, stairs, arbor and possibly also the freely undulating paths of an English park up to the Belvedere on the north Edge of Černopolní.

When Alfred and Marianne Löw-Beer bought the Art Nouveau villa in 1913 and moved in with their children Max (11), Grete (10) and Hans (12 years old), they probably left the garden unchanged.

In 1929-1930 Grete Müller-Roder took over the path system of the English Park, simplified it somewhat, introduced a kitchen garden in the area of the service wing, and along the base of the house a terracing with dry stone walls, perhaps an allusion to the historic vineyards. The floor plan of the Tugendhat house is clearly based on the axis relationship between the semi-circular dining area and the weeping willow, which was already large at the time and was Grete Tugendhat's favorite tree. Grete Müller-Roder also planned the seating area under the weeping willow, with direct access via a staircase through the terracing and a further path. A (no longer preserved) closed vegetation to the neighboring properties created the privacy of the garden space, which was understood as a meaningful emptiness, which was certainly desired by the client.

In this context, it is also worth remembering the excellent planning work of Přemysl Krejčiřík and his team during the recent restoration of the garden in 2010-2012.

I would also like to understand the opening of the garden between the two houses in a general, symbolic and social sense: as a mental opening of the gates and also as a real opening of the borders where it is necessary for cultural and humanitarian reasons.

Thank you for your attention.

The New European Bauhaus (NEB): beauty, sustainability and cultural heritage through the prism of Villa Tugendhat (Brno, November 21, 2022)

The New European Bauhaus (NEB): beauty, sustainability and cultural heritage through the prism of Villa Tugendhat

High-level gathering on 21 November 2022 from 14:30-18:00 in Brno, Czech Republic. Tugendhat House

Programme:

14:30 Arrival and guided tour through Villa Tugendhat (Daniela Hammer-Tugendhat and Ivo Hammer)

16:00-17:00 High-level panel discussion

17:00-18:00 Reception

The New European Bauhaus (NEB) is a creative and interdisciplinary initiative of Ursula von der Leyen, President of the European Commission. It connects the European Green Deal to our living spaces and experiences. The initiative calls on all of us to imagine and build together a sustainable and inclusive future that is beautiful for our eyes, minds, and souls.

Architectural purity, interconnection of interior and exterior, timeless technical equipment, noble and exotic materials and, above all, a high level of preservation – these are the main attributes that led Villa Tugendhat to being inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List in 2001. Designed by the German architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Villa Tugendhat was built in 1929–1930 as a family home for Grete and Fritz Tugendhat. Its further history is at least as fascinating as its cultural significance, since it has become Brno’s icon of modernist housing and occupies a prominent position globally and within the oeuvre of its architect.

Our gathering “The New European Bauhaus: beauty, sustainability and cultural heritage through the prism of Villa Tugendhat” will, against the backdrop of this emblematic property, explore the goals, philosophy and perspectives of the New European Bauhaus initiative, illustrating and reimagining sustainable living in Europe and beyond. (Martin Selmayr, Head of Representation of the European Commission in Austria)

Ivo Hammer, REPAIR – RE – TURN / POROSITY – RE – TURN

Statement Ivo Hammer, 21.11.2022, Brno, Tugendhat House, panel

Ladies and gentlemen

I would like to thank you for the invitation to this event and to Martin Selmayr for the friendly introduction.

My short statement is based on the question:

What can we learn from monument preservation in general and from Haus Tugendhat in particular

What can we learn:

- for dealing with existing buildings

and what can we learn

- for beautiful, sustainable and inclusive new buildings?

First, a few comments on the materiality of the Tugendhat house:

The beauty of the house of Tugendhat is not only based on the 1930 new design. Its beauty is also based on its materiality: on the use of noble materials such as onyx marble, travertine, tropical woods, silk, parchment and polished chrome and nickel, and on the extremely precise craftsmanship of all traditional surfaces, the polished stucco lustro of the interior walls, the careful material-colored painting of the metal and wooden parts. Bright colors brought life, brought individual furniture, flowers and, yes, the residents and their clothing.

Many elements, such as the walls of the interior and the facade, are made with exceptionally careful, but still traditional craftsmanship. They can be maintained and repaired accordingly without great effort, without them being changed in an aesthetically or physically unfavorable manner. Stains on the interior walls e.g. For example, during the short period in which the Tugendhat family was able to live in their house, they were erased with bread; no painting was necessary.

The inner walls are not only beautiful, they are also pleasant for the room climate due to their hydrophilic porosity, which is permeable to water in liquid form, because no condensation can form on the surface and therefore no microorganisms either. (Allergies!)

The brick exterior walls are traditionally coated with rubbed lime plaster and painted with limewash. Unlike cement, which contributes 8% to global CO2 emissions, lime is largely CO2 neutral.

The facade of the house T. has been cared for several times with whitewash, also during the time when it was used as a dance school and as a children's hospital from 1945-1980. Significant damage only occurred after 1985, when the facade was coated with a modern paint containing synthetic resin as a binder. In 2011 we reintroduced the traditional form of periodic care with a lime wash.

Remarks on the current situation of the construction industry in terms of materials and technology.

We have been experiencing radical, dramatic changes since the 1960s. The historical tradition of periodic maintenance and repairs has been abandoned (as in other areas). The lack of care and repair leads to rapid wear and tear and the corresponding waste of resources and energy.

The use of historically proven materials has been abandoned in favor of incompatible materials that are physically, chemically and aesthetically incompatible with the historical structure and lead to serious damage to the old buildings (cement, artificial resin). Coatings that are not hydrophilic, i.e. permeable to water in liquid form, lead to accelerated weathering (drying speed reduced by a factor of 1000!) and destroy the historical surface in the long term. Thermal insulation, very often a fire hazard (Grenfell Tower in London!), is obsolete from an insurance perspective after 40 years, and technologically often in a much shorter time. Plastic windows and doors are not repairable.

The new buildings are based on short-term economic calculations and accelerated obsolescence. We live in concrete buildings and plasterboard walls and plastic coatings. The non-hydrophilic surfaces (in addition, mostly small and low living spaces) lead to the growth of microorganisms and promote allergies and make frequent shock ventilation necessary.

My thesis on dealing with old buildings

Monument preservation can be seen as a paradigmatic form of a sustainable, ecologically meaningful and aesthetically beautiful way of dealing with historical architecture,

e.g. with regard to the following categories:

- Maintenance of the long service life through regular care and repair with materials and methods that are compatible with the historical structure and preserve the repairability, instead of cosmetic interventions with physically harmful and aesthetically disturbing materials. The technological characteristic of the historical buildings is their hydrophilic porosity.

- Reuse of materials in reconstruction and adaptation. The recycling rate of a historical building is approx. 95%, a modern new building often only approx. 5%. (Kohler, 1996). Separability and harmless dumping of materials that can no longer be used. (Today, building rubble is hazardous waste that requires monitoring).

- Intelligent cultural use instead of short-term economic speculation. Avoidance of energy loss (calculated over the long term) and gentle adaptation to new usage requirements. The most ecological form of building is not building.

My thesis on the new buildings:

The environmental policy of monument preservation is also relevant for the new building.

The architectural monuments represent approaches to solving technical, aesthetic and other cultural and social (e. g. also urbanistic) problems. The experiences of around 15,000 years (Göbekli Tepe) are stored in the monuments, which have proven their technological suitability and their cultural suitability with their mere existence. Why shouldn't we use these sources of knowledge?

Some demands for a sustainable construction industry

- The building materials industry and materials science should focus on sustainable traditional materials such as lime, wood and clay

- While the technical standards correspond to many building materials designed in the laboratory, they are often nonsensical for historical techniques

- Tax law, tenancy law: old buildings are disadvantaged

- Funding provisions: Funding should be aimed at projects that are sustainable in the long term

- Economic research should calculate with the entire life cycle of a building, not just a part of it.

- Educational System: Architecture, its beauty, history and sustainable repair should become part of the normal educational curriculum

- Architectural training, craftsman training should include historical techniques, repair materials and repair techniques in their curriculum

- In many European countries and also internationally, university courses for the preservation of historical architecture are set up only for architects. There are no courses for conservators-restorers of architectural surfaces. (except Hildesheim, Vienna, Munich)

- Aesthetic norms: aesthetics of repair, practical value instead of novelty value

The projects that have won awards as part of the NEB are inspiring, but often standalone actions. They should go mainstream.

For a sustainable and ecologically sensible construction industry, we need

- methodically a re-use re-turn and repair-re-turn

- technologically a porosity re-turn (i.e. hydrophilic porosity, permeable for water in liquid form)

Ivo Hammer, The (male) visible and the (female) invisible. Remarks to the cooperation of Lilly Reich and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe using the example of the Tugendhat House in Brno (Virtual, February 4, 2021)

The Mies van der Rohe Society, in partnership with Illinois Institute of Technology College of Architecture, sponsored an evening through the lens of acclaimed filmmaker, June Finfer (alumna), with footage of the Tugendhat House—considered one of the most influential homes of the 20th century—designed by Mies van der Rohe and Lilly Reich.

Lilly Reich’s award winning work with Laura Lizondo-Sevilla and Débora Domingo-Calabuig (Universitat Politècnica de València) were also discussed.

Commenters included art historian Daniela Hammer-Tugendhat and her husband Ivo Hammer, conservator-restorer and art historian, who was working to maintain the Tugendhat House; as well as Jong Soung Kimm (ARCH ‘61, M.ARCH. ‘64), Dirk Lohan (alumnus), and contributors from Illinois Institute of Technology College of Architecture: Reed Kroloff, dean; Martin Felsen, director, Masters of Architecture Program; and Michelangelo Sabatino, professor. https://www.miessociety.org/events/lilly-reich-lecture

Mies van der Rohe Society, Chicago

Interiors: Lilly Reich and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe (Virtual)

Thursday, February 4, 2021

Speech of Daniela Hammer-Tugendhat

Ladies and gentlemen,

I am delighted that this important event can take place, and I would like to thank Magaret and Dave Hensler for making this

event possible and Cynthia Vranas and her team, who worked tirelessly to make it happen.

I will not talk about the significance of Lilly Reich and her importance for the Tugendhat House – I leave this to the experts.

But I would like to point to a more general issue: The invisibility of Lilly Reichs contribution on the Tugendhat House is by no means an individual problem between Mies van der Rohe and Lilly Reich. It is a structural problem of patriarchal gender inequality. Women were – and often still are – not meant to be artists, for sure not architects, this godlike profession of male ingenuity. Other great woman architects of the 20th century shared the same fate: think for example of Margarete Schuette- Lihotzky or Eileen Gray. Woman painters of the last centuries highly estimated in their own time like Sofonisba Anguissola at the end of the 16th or Artemisa Gentileschi or Judith Leyster of the 17th century, have been wiped out of the cultural memory by art history. By centuries we internalized these mental structures, so even now in the 21 century we find it hard to accept artistic equality between male and woman artists. I do hope that after this little but important conference nobody will speak of the Tugendhat House by Mies van der Rohe – but the Tugendhat House by Mies van der Rohe and Lilly Reich.

CIC

Si quis vel mediocriter doctus erit hanc rem facile intelleget

THICOM

Si quis vel mediocriter doctus erit hanc rem facile intelleget

Materiality

Si quis vel mediocriter doctus erit hanc rem facile intelleget